"SELLA DORE — Mysteries of Many Kinds": Series Introduction (and the first story, "Left Her Heart")

From the unpublished book "SELLA DORE — Mysteries of Many Kinds" by A.S. Kaswell, as transcribed by Marc Abrahams

Tiny Introduction

I don't know what you will make of these.

The whole thing, I guess, is a skimpy record of some of the problems people have dumped on Sella Dore's lap, and the solutions that Sella then dumped on their heads.

I got to be there while Sella deployed her absurdly practical good sense. Sometimes I even got to help.

There are more of these stories, too.

But I haven't told those to anyone. Yet.

Enjoy, or whatever.

— A.S. Kaswell (translated by Marc Abrahams, from the original English)

PS. In writing these accounts, I was struck by the echoes in Sella's life (and by proximity, in my life, too) of mystery stories I consumed as a child. Those fictional heroes have failings: they are fictional, and they lack Sella’s boundless knowledge of 20th and 21st century scientific research.

Left Her Heart

"What a mess," said Sella Dore, gazing through, or for all I could tell, at, the office window. "She left her heart, Kaswell, and for all I could tell, her senses."

"Sella," I said, "I have no idea what you're talking about."

Sella often does this to me, for her mild amusement. I am her assistant. She is (as you probably know) Sella Dore, the mildly-celebrated consultant on little and big matters that stymie the problem-solving talents of detectives, doctors, business leaders, and other theoretically brilliant humans. Sella's unusual talents emerged way, way back when she was the purchasing expediter for a small company.

Sella took a slow, slow sip of tea.

"I am talking about a story, Kaswell, A story barely half-sketched for me by a woman who is coming here today, to consult me about a problem, apparently. Ah! I hear footsteps, which are the best kind of steps, approaching the door. Kaswell, would you please welcome Marlene Barberish, MD, and bid her sit down?"

It's a good sign when someone finds their way to the elderly office building where Sella has her office at the good end of the long corridor on the middle floor. It's not a good sign when someone can't manage that. Today started off okay.

The door opened. A lab-coated thirtyish woman, her head enveloped with nondescriptness, minced in, said, "I am Doctor Barberish. One of you is Sella Dore?", and looked self-invitingly at the oak visitor's chair next to Sella's desk.

"Sit down," I said. "One of us is Sella Dore."

The woman looked at me, rubbed her chin with the knuckles of her left hand, and said, "Okay." And sat. Then she peered down into the plastic bag she'd brought along, and placed the bag on Sella's desk.

Sella and I waited. Sella, the very picture of patience, relaxed in her chair, and fluffed the lapel of her long hunter-green housecoat. The woman looked up, but not at either of us, and said: "My heart is broken."

She lifted from the bag a dripping, hand-size, reddish/pinkish/gray glop, and laid it on Sella's desktop. "I suppose it's mine," she told us. "Doesn't matter now, cause it's broken."

Sella nodded. "Yes, I can see that, Doctor Barberish. I am Sella Dore. This is my assistant, Kaswell. Kaswell, would you let Macrophage come in."

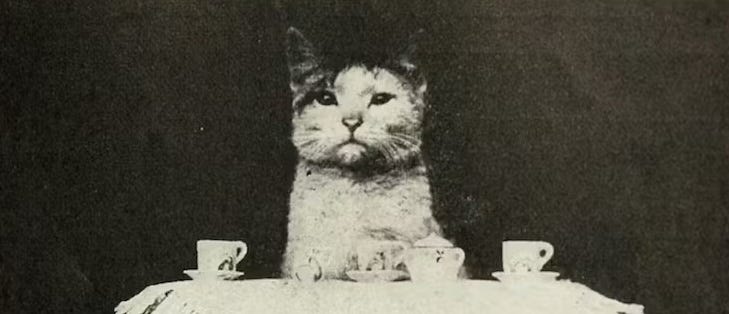

I went to the door, and opened it. Macrophage came in. Macrophage is the twelve-pound brown-and-white cat that spends his days among all the offices, even Sella's, in the building. We don't know where Macrophage goes, or stays, at night.

Macrophage parkoured from the floor to the desktop, and began making an efficient, slow meal of the remnants of what Doctor Barberish had told us was her broken heart, alternating small bites of the flesh, or the fleshy-looking part, with studious sips of the drip spreading across Sella's desk, and with licks at some of Sella's papers that were sopping up the wet.

"Welcome, Doctor Barberish," said Sella. "I suppose I should thank you for dumping this mess in our laps."

"Be accurate, Sella," I said. "It's on your desk."

"Somehow, I don't know what to do," said Dr. Barberish.

"Tell me your tale, Doctor Barberish," said Sella. "Include enough information that Kaswell here can comprehend the oddity."

"That's a nice way to put it," Dr. Barberish smiled. "Comprehend the oddity."

"I founded the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine," began Dr. Barberish. "Well, not by myself. We had investors, my Aunt LeeAnn and Uncle Ralph. They bought all the equipment, and they assist me in the management and business aspects — for those are fully as needed as the medical aspects if a medical school is to remain alive and healthy, you know. There is also my sister Amy, who brought to the venture her nearly-a-year of extensive experience assistant managing a McDonald's restaurant, a milieu in which complicated functions, high pressure, and sudden life-and-death dramas are as frequent as in any big city hospital."

"Indeed?" said Sella.

"At the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine, we pioneered — and are still pioneering — a new and better way of teaching medicine. We teach in the milieu in which over seventy percent of all medical incidents and chronic occurrences occur. To wit, in the homes of sick, dying, and dead people," Dr. Barberish said.

"You conduct all your medical lessons in the homes of sick, dying, and dead people?" I said, mostly to myself.

"Precisely," Dr. Barberish praised, "That is the milieu. And realizing that all existing medical schools do basically the same things as all the other existing medical schools, and that all existing medical schools basically *neglect* to do certain *other* things, I realized that there is a shortage of, and a need to train and carry out some of those neglected, *other* vital medical activities. To wit, postmortems on the kitchen table."

"Do tell," said Sella.

"I will tell you about that," said Dr. Barberish.

She told us about that. In detail. For seven hours. We had a meal delivered around noon, and coffee about two hours after lunch, and then another meal some hours after that.

Several times, Sella and I took a little pause to boil a new batch of water in the electric kettle that shares half-ownership of my desktop with the Mason jar that hold some of our used teabags and with the fleet of mugs that hang out there with the Mason jar.

Dr. Barberish, who had explained to us, each of those several times, that no, she does not drink tea during weekdays, and that some people find it surprising that yes, she does sometimes drink tea on weekends, remained seated. She did a slow visual survey of our office, especially the full wall of full shelves behind Sella's desk.

"Sella, I am fascinated by the large collection of miscellaneous objects that fill your shelves," she said.

"Most of those things were here long before me," Sella explained, "probably abandoned by the series of businesses that have occupied this space. I know little about any of those businesses, save for the detritus they left behind."

Dr. Barberish gave a little squeal. "Look at those Mason jars! Green glass Mason jars! Just like my Aunt Barbara used for pickled beets!"

"The jars here are quite old, probably older than your Aunt Barbara's," Sella said. "It's possible these were manufactured here. There's also a copy of John Landis Mason's patent — the patent for the Mason jar — which was granted in the year 1858. U.S. patent number 22186, if you're curious."

Dr. Barberish shook her head dismissively. "No one cares about that. I notice that you use one of those Mason jars to hold wet teabags. That's a good reminder to me that you can use Mason jars to keep important things moist. It makes me realize that there are several good uses to which we could put them in the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine. I think you should donate some of your Mason jars to the school. They are so practical. The students would love them."

Sella gazed at Dr. Barbarish for a few moments, then said, "I think not."

Sella and I took our tea mugs back to our desks, and brought the hearty discussion back to Dr. Barberish's situation.

I will try to summarize the mundane but essential core of what Dr. Barberish outlined at length for us about what she said she views as the essential core of her work.

Dr. Barberish explained that postmortem examinations, to identify the cause of death of dead persons, used long ago to be commonplace, but that as costs rose, fewer and fewer dead people and their families were treated to postmortems. Yet so many of those dead people and their families would have loved to have known more about the cause of death!

The way to make everybody happy, Dr. Barberish explained that she realized, was to offer people so-called "amateur" postmortems right in the convenience of their homes. Many families would find it easy to make the decision to order a home postmortem if they were offered it at just the right, best moment, soon after their relative died. And many dying people would find it easy to themselves order in advance, as a kindness and a treat for their families, if they, the dying people, were presented at just the right, best moment with a lively explanation of the benefits. And almost every family has a kitchen table.

Dr. Barberish explained that it was important that everybody realize that their home postmortem would be performed in a manner that clearly looks professional, yet clearly is billed, on a per-minute basis, at a rate so low compared to prevailing hospital tabletop rates that the final amount on the bill looks, to everybody making even the slightestly-knowledgeable comparison, to be "amateurish." Thus the name, the proud name, that Dr. Barberish and her Aunt LeeAnn and Uncle Ralph, and her sister Amy, chose for the school. They would call it the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine.

Dr. Barberish further explained that the performances of the postmortems would genuinely be performances, with the surviving relatives welcome to gather round the kitchen table, see for themselves the fine quality of the work as it is being done, and have snacks and drinks. All of this, pointed out Dr. Barberish, would be educational.

"I think I understand what you are doing, and why," I said, at about the six-hour mark of Dr. Barberish's explanation, though in retrospect and even at the time, I think maybe I did not. "But — and pardon me if I somehow failed to appreciate this — I am not clear on why you want to consult Sella Dore. What is the mystery you wish to solve? What is the dilemma?"

"In other words," Sella herself stepped into the conversation to say, "What's your problem, Doctor Barberish?

"Ah," said Dr. Barberish. "I'm glad you asked me that. Here's my problem."

"Yes?" invited Sella.

"Cats," said Dr. Barberish.

"Cats?" said Sella.

"Cats," said Dr. Barberish.

"I'd like to put my three cents in," I said. "Cats."

"Hush, Kaswell," muttered Sella. Dr. Barberish seemed not to notice Sella's snippiness.

"Doctor Barberish," said Sella, "Do you have a problem with the cat that was here a few hours ago?"

"Cat?" inquired Dr. Barberish. "What cat?"

"Doesn't matter," waved Sella. "Tell me about your problem with cats. Please."

"Let me tell you about my problem with cats," said Dr. Barberish. "I am a stickler for clarity."

"It seems to happen more in the summer," she began. "On some summer days it gets pretty hot in some of those kitchens, as you might expect. Especially when there's a big gathering of family members crowded into a crammed little kitchen, especially when the decedent is in a condition that calls for, requires really, some pretty vigorous activity when you're performing the postmortem, and especially especially when some of the family and friends are contributing some pretty vigorous activity to help out. So what I often do, on that kind of day, in that kind of situation, is take a break about midway, and suggest we all go out for a stroll and buy ourselves ice cream cones. The family and friends almost always pay for the ice cream, and they're happy to do it. We all come back to the kitchen, after the ice cream, in a happy mood. It's a happy thing to do on a hot summer afternoon."

Sella prodded: "You suggested there is a problem with cats."

"There is a problem with cats," agreed Dr. Barberish. "Especially on that kind of summer day, in that kind of situation. Especially when we all go out for ice cream. Everyone is so eager to go that sometimes the family members neglect to close the door. Everyone is so eager for ice cream. And that's where the problem comes. That's where the cats come in. Sometimes cats come while we are all out eating ice cream, and sometimes those cats are hungry. And did you know that cats are fascinated by hearts, especially human hearts? Cats love human hearts."

"I see you have a problem there," said Sella.

"I'm glad you understand," said Dr. Barberish. "But," she continued, "cats are an everyday kind of problem, and mostly only in the summer. Mostly. But cats are not the problem that made me want to come here today, to consult you."

"I should feel relieved," said Sella.

"That's not for me to say," said Dr. Barberish.

"The thing that's biting us in the haunch right now, professionally, logistically," said Dr. Barbarish, "is what happened at McDonald's."

"McDonald's," said Sella.

"Yes, said Dr. Barberish. "I told you that my sister Amy had nearly a year of extensive experience assistant managing a McDonald's restaurant. And that was before we began operation of the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine. Amy has almost three quarters of a year of experience now."

"Uh huh," said Sella.

"I may not have mentioned that our business is a great success. I mean as a business, not just as a medical school. The Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine has an auxiliary line of business, supplying parts to other medical schools. We supply amateur medical schools, not just professional medical schools. We supply them with whatever is in short supply, and in practice that mostly means hearts, supply and demand being what it is these days."

Sella looked quizzical. "It is not immediately obvious to me," she said, "how McDonald's enters into this picture."

Dr. Barberish brightened. "When was the last time you ate at a McDonald's?" she asked Sella.

Sella lofted a brow. "It's been a while. A matter of years."

Dr. Barberish brightened even more. "Then you may not realize what relaxing places many McDonald's have become, when a person is busy transporting lots of parts, in the supply chain, and needs a break. The McDonald's where my sister Amy has extensive experience assistant managing is an especially relaxing place.

"Anyway," said Dr. Barbarish, "the problem happened at a different McDonald's, though my sister Amy was… involved. My sister Amy ships — personally transports, really — most of the parts that we deliver, in the supply chain.

"A few days ago," Dr. Barbarish continued, "Amy was transporting a nice fresh dead heart to a hospital that had ordered it, for a transplant, I think. She carried it in a cooler, the way one does when one is transporting parts professionally, in the supply chain. As you'll see, Amy was, obviously, not as careful as she should have been. Amy was hungry, so she stopped to buy a cheeseburger at a McDonald’s — not the McDonald's where she has the extensive experience, but as I said, a different McDonald's where she has no experience, and where she was just a customer. Amy was hungry. She left the cooler containing the heart on her seat while she took a short trip to the rest room. When Amy got back from the rest room, she was in a hurry and forgot to go back to her seat and pick up the cooler.

"Arriving at the hospital, with the hospital team eagerly awaiting her arrival with the part, in the supply chain, Amy awoke from her triumphant, supply-chain-delivery reverie, and realized that she had left her heart in the McDonald's, on that seat. She decided to return to the McDonald's, for the heart. When she got back to that McDonald’s, it had closed for the day.

"The next day, the cooler was not there. Amy was waiting at the door when they opened in the morning! None of the employees remembered having seen the cooler, or the supply chain part it contained.

"I brought a substitute heart with me today — should have mentioned that earlier — to give you some context. It's from a kitchen procedure we did this morning. It's a leftover, actually. Just a leftover. I was going to leave it with the family of the decedent, but for some reason they didn't want it."

Dr. Barberish's manner was becoming almost whimsical as she explained this to us. Me, I wasn't sure I wanted to hear a lot more.

Sella, I saw, had something to say.

"Doctor Barberish," said Sella. "I'm going to interrupt you. I realize you have just begun to tell us about your problem. It is a problem that undoubtedly deserves more than seven hours of exposition. Before you do get to the nub of it, there are a couple of things it might be helpful for me to point out.

"The first thing," said Sella, "is that you are following a noble tradition, in a way. Likely you are aware of Arthur Holloman's essay published in the *British Medical Journal*. No? Not familiar? Ah, well. The title of Holloman's essay is 'Postmortems on the Kitchen Table.' I recommend it, if only for your pleasure.

"The second thing is, Doctor Barberish, let me ask you a personal medical question," said Sella.

"You want to ask me a medical question?" asked Dr. Barbarish. "Well, I usually charge for medical consultations, especially if the person is alive. I try to be consistent about that. It's good business practice. But of course, you are being so kind as to let me partake of your own expertise, which though it is on a lower level of expertise than medical expertise, I'm sure has worth. And I appreciate that. So yes, you may ask me a personal medical question."

Sella looked squarely at Dr. Barberish.

"Doctor Barberish," Sella said, "Do you have a medical degree?"

"Do I have a medical degree?" Dr. Barberish said, stiffening. "You have nerve, Sella Dore. Gall, even. Of course I have a medical degree."

"Where did you do your medical training, Doctor Barberish?" Sella asked.

Dr. Barberish relaxed, pride and friendliness suddenly emanating. "I have a medical degree from the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine. It has stood me in good stead."

Sella quasi-cocked an eyebrow. "You have a medical degree from the Dr. Barberish Professional Amateur Schools of Medicine."

Dr. Barberish, frowned. "There is no need to repeat my words back to me. Why are you repeating my words back to me?"

Sella smiled. "Because yours is a delightful statement, and delightful statements deserve to be twice told. Now that I have heard this statement about your medical degree twice, it is doubly delightful."

Sella turned to me. Sella glowed. "You see, Kaswell, this convoluted situation, when properly considered, turns out to be not convoluted. And not even a situation, really."

"You and I share a sensibility, Sella Dore!" Dr. Barberish chirped.

I stood up, casually, looking vaguely at the table that, hours earlier, had hosted our local cat. "Sella," I said, "Simplify this for me. What is the story here?"

"The story, Kaswell, is simple. Quite simple. That woman is a nut."

"Sella Dore!" Dr. Barberish groaned.

"Sella Dore!" Dr. Barberish grunted.

"Sella Dore," Dr. Barberish growled, "You are heartless."

Sella nodded, and continued nodding. Eventually, I realized that the nodding was meant to direct our attention to the plastic bag that Dr. Barberish had brought. The bag still lay upon Sella's desk, but now, thanks to the efforts of Macrophage the cat and the subsequent seven hours of evaporative drying of the dampness that Macrophage's foraging left behind, that bag was empty and no longer wet.

Sella stopped nodding, and looked up from the bag, to gaze at Dr. Barberish.

"Me, maybe," said Sella. "You definitely."

(Before you get hot and bothered: yes, the Sella Dore stories are fiction. If you want to see more of Sella’s adventures, please let me know! )

(Copyright 2025 Marc Abrahams)

A paid subscription costs about the same as a fancy coffee each month.